The trailblazer: James 'Jimmy' Peters

24 October 2023

We're celebrating the story of Jimmy Peters at The Box this half term. Read on to discover more about the extraordinary life of the first black man to play rugby union for England.

Jimmy Peters had a difficult start in life but, showing great strength of character, he overcame hardships, setbacks and intolerance to represent his country with distinction.

He was born in Salford in 1879 to a West Indian father, George Peters, and an English mother, Hannah (née Gough). During Jimmy’s childhood, his father is recorded variously as a traveller or a labourer on official documents and it is widely believed that he worked with a travelling circus. Records show that the family moved frequently – from Salford to Liverpool to Bristol – and at times, they were living intriguingly close to the stopping places of a famous travelling show called Wombwell’s Menagerie.

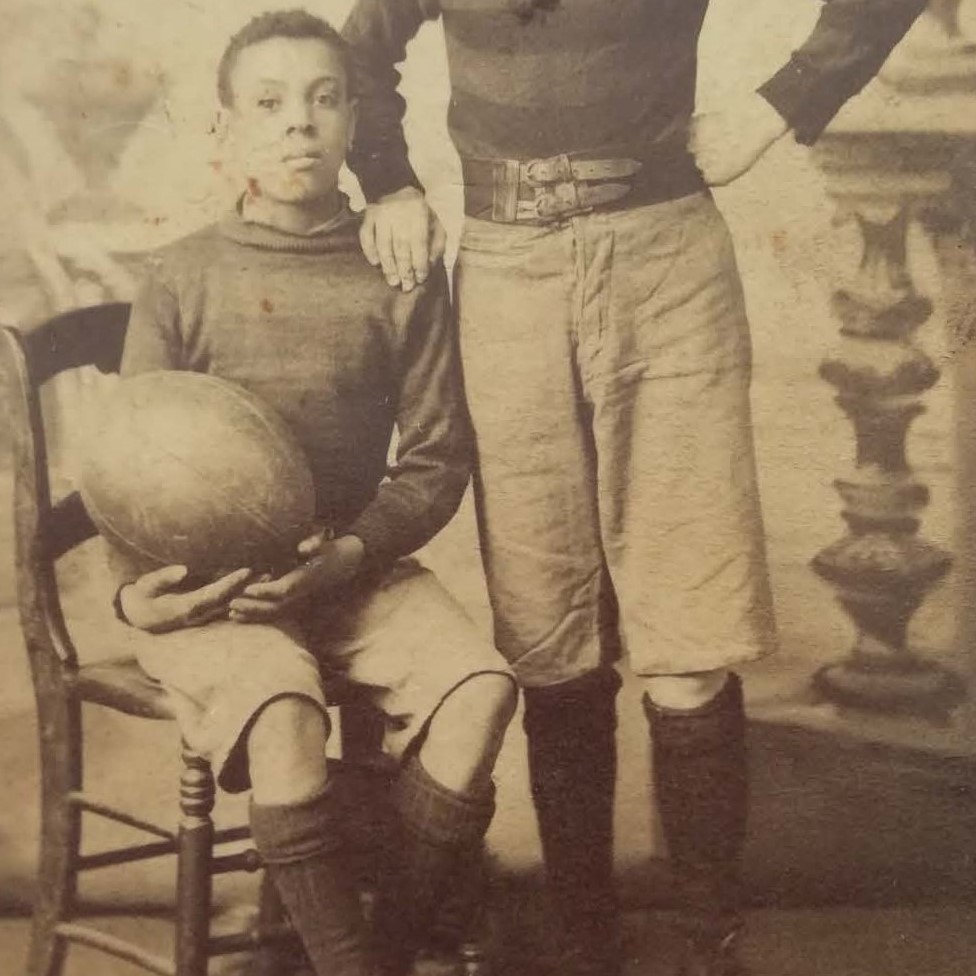

According to an account of Jimmy’s childhood written in the 1890s, George met with ‘a shocking death in a lion’s cage’ – though an incident matching these details has not been found in any contemporary newspaper articles. After his father’s death, Jimmy moved to another circus troupe, where he performed as a bareback horse rider. Shortly afterwards, when a broken arm had left him unable to perform, a kind lady found him tied up outside a circus caravan and arranged for him to be rehomed.

Jimmy arrived at Fegans orphanage, London, in November 1890. As well as orphaned boys, Fegans welcomed those who had fled cruelty at home and those – like Jimmy – with a living parent who was unable to support them. Skills taught at the Home included printing, carpentry, shoemaking, and tailoring. The skill of carpentry became Jimmy’s trade in later life.

It was at the children’s home that Jimmy discovered rugby. Fegans boys were allowed free entry to matches at Blackheath and their interest soon evolved into an enthusiasm to play themselves. Jimmy spent time at both the Little Wanderers Home in Greenwich and the Southwark Boys’ Home, where he was trusted to be Mr Fegan’s door boy.

Jimmy’s aptitude for sport was clear at an early age. The Rescue, a newsletter distributed by the Home, states that:

Jimmy Peters is the champion athlete. He seems constructed differently to other humans – all joints and springs inside…

In the days before the scrum half and fly half positions became distinct, Jimmy played in the position of half-back – one of two players who organised the game on the field.

Jimmy left Fegans Homes in September 1898 and moved in with his mother, stepfather and siblings, who were living in one of the most deprived parts of Bristol. In 1897 the Shaftesbury (Christian) Crusade had founded a rugby club called Dings Crusaders, where Jimmy played in the 1900-01 season. During his time in Bristol, he played for both Knowle and Bristol RFC.

Jimmy was subject to racial intolerance at various times during his playing career and some of Bristol’s committee members are said to have resigned in response to his selection. Despite the objections to his selection, Jimmy developed into a highly skilled and intelligent half-back. He went on to make 35 appearances for Bristol from 1900 to 1902 and was also called up to represent Somerset County.

In 1902, Jimmy moved away from Bristol and settled in Plymouth. He joined Plymouth RFC and remained with the club for over ten years. He played for Somerset one more time before being selected for Devon, his new county, in 1903. His second match at Devon saw him partnered at half-back by Raphael Jago – it was the start of a formidable long-term partnership for the county team.

In the years that followed, Jimmy’s accomplished performances received favourable press coverage and local newspapers began to call for his England selection. Jago was called up to make his international debut in England’s match against Wales in January 1906, but his fellow Devon half-back was not chosen. Some newspapers in the southwest considered Jimmy’s non-selection to be racially motivated.

Jago and Peters … stood out in strong contrast to the other pair of halves, and the opinion was expressed all round that they ought to play together for England next Saturday. The powers that be, however, have decided otherwise. Peters is sacrificed. Colour is the difficulty ... Pity for the chances of the English success.

The Western Times, 05/02/1906

Jimmy’s talent had not gone unnoticed by the England selection committee, however. He had become a dominant player within the Devon team and following their victory over Durham in the County Championship final, he was invited to play for England in March 1906.

On his debut, Jimmy helped the national team to a victory over Scotland at Inverleith, winning the Calcutta Cup for the first time in four years. The team followed this up with a win against France at Le Parc des Princes – the first time England and France had met in international rugby. On a day when windy weather compromised both passing and kicking, Jimmy contributed one of nine tries scored by the English team.

At international level, Jimmy proved himself to be an intelligent and creative footballer, and an elusive, athletic runner. His ability to read and control the game had guided England to two long-awaited victories.

England’s next match was against the touring South Africa team in December 1906. Jimmy was not selected for the trial matches nor for the international Test. Inevitably, it was speculated that he was dropped in response to objections from the touring side, but this is not definite. He may have had a dip in his form, or simply the England selectors wished to try different player combinations.

Jimmy was called up again to play for England on three further occasions. The match against Ireland in 1907 was the only time he lined up for the national team alongside county teammate Raphael Jago. When England lost to Scotland at Blackheath in their next match, Jimmy scored England’s only points and his last-minute try was the only one conceded by the Scots that season. He made his final international appearance against Wales the following year.

Jimmy continued playing for Plymouth and Devon, but his rugby-playing days appeared to have been cut short when he suffered a workplace injury in February 1910. He lost three fingers in an accident with a steam planing machine at the Matcham and Co. work yard. Plymouth arranged a testimonial match to support Jimmy while the debilitating injury left him unable to work. With the RFU viewing the benefit payment as an act of professionalism contrary to the sport’s strict amateur regulations, he was banned from further participation in rugby union. In 1912 the RFU expelled or suspended 38 players and officials in Devon, including Jimmy. Plymouth RFC was closed down.

Undeterred, he moved to the north of England to play rugby league professionally. In 1913, at the age of 34, he signed for Barrow and in 1914, he made two appearances for St Helens before retiring from rugby.

James Peters was the favourite of the crowd and right well he deserved their favouritism. Everything Peters does is with cleanness and nippiness ... His side-step is bewildering, and his passes are so swift that at times they are not taken … his place kicking is inclined towards the phenomenal.

Barrow Herald, 15/11/1913

After his brief rugby league career, Jimmy moved back to Plymouth and was employed at the Royal Naval Dockyard during the First World War, including some time at the Royal William Yard – the victualling yard – where he might have been producing crates and barrels to store supplies.

After the war, Jimmy remained in Plymouth, where he lived for the rest of his life. He is still recorded as a carpenter in 1939 (Findmypast.co.uk) but after this it is claimed he became a publican – but was himself teetotal. In 1907, he had married Rosina Finch at St Jude’s, Plymouth. They were married for 47 years and they had two children, Rowena and Jimmy.

Jimmy’s granddaughter Barbara remembered him fondly:

I have always been proud of him, he was a lovely man, so kind. He spoiled me rotten… He had a very tough start in life, but he overcame it and was a friend of anyone and everyone.

Jimmy died in 1954, at the age of 74, and is buried in Ford Park Cemetery. In 2015 a gravestone was installed to pay a fitting tribute to the achievements of England’s first black international rugby player. Much-admired as a player and a person, he is remembered today as a trailblazer. It would be 82 years after Jimmy’s first England appearance before another black man, Chris Oti, was called up to play for the national team.

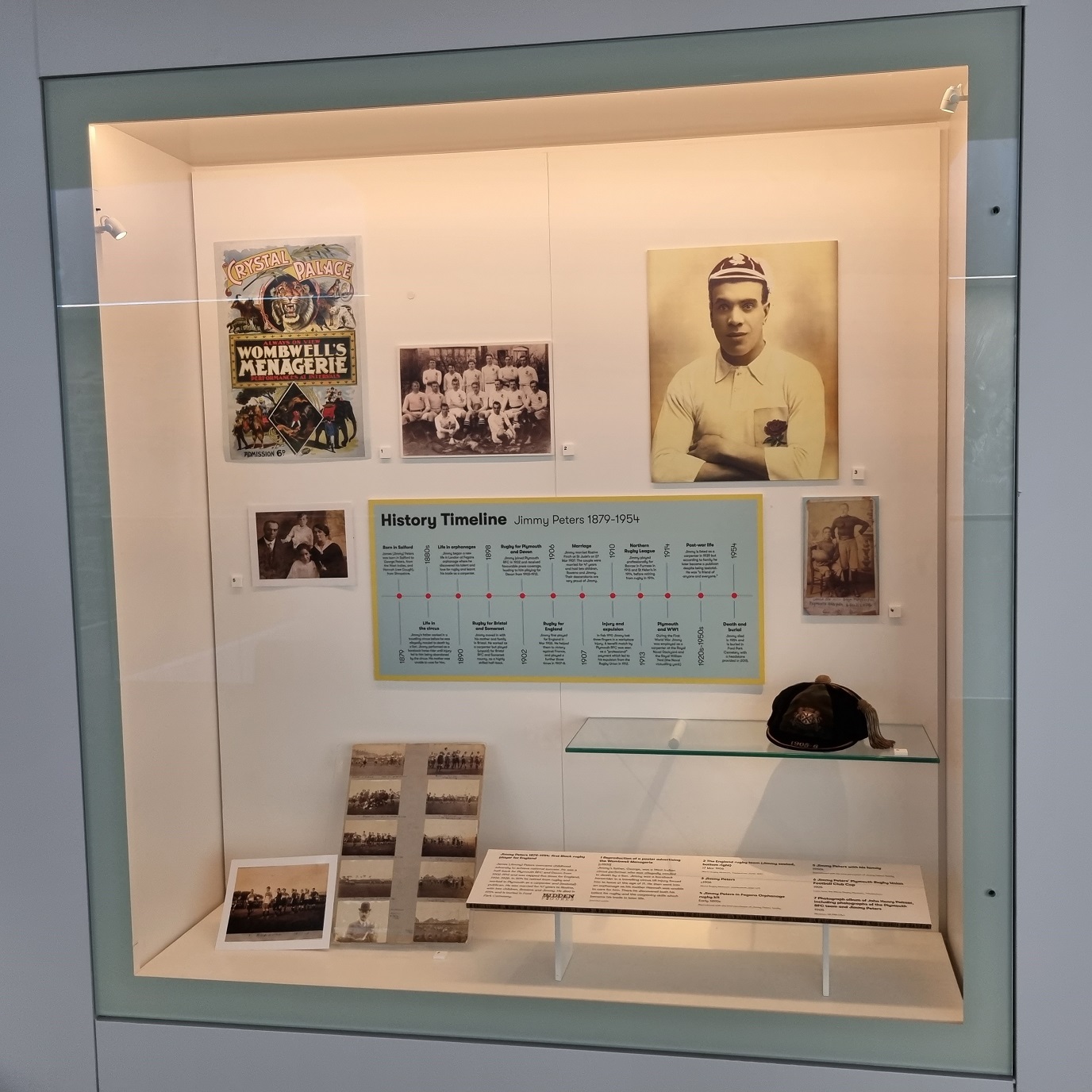

Jimmy is one of the Plymothians selected for inclusion in the Heritage Lottery funded Hidden Figures project. A case display about his extraordinary life can be seen in our Active Archives gallery until 2 January 2024. It includes Jimmy’s Plymouth RFC cap, kindly loaned by the World Rugby Museum, Twickenham, plus photographs generously provided by Jimmy’s family, as well as an exciting discovery from The Box collection.

There is also currently a display about Jimmy at the World Rugby Museum, Twickenham.

Thanks to Niamh Field, World Rugby Museum, Twickenham, with additional content from Claire Skinner, Archivist at The Box